William Brown: Black Saloonkeeper on the Comstock Lode

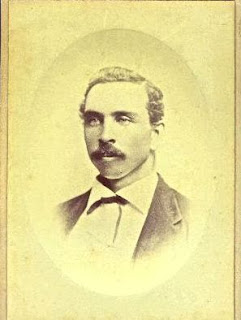

In 1862 two men who found themselves in Virginia City, Nevada each made that Comstock Lode mining town the launching pad for their careers. One was Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, the Nation’s most famous author. The other was William A.G. Brown, shown here, an African American saloonkeeper who languished in obscurity until Nevada archeologists excavated the site of his drinking establishment.

In 1862 two men who found themselves in Virginia City, Nevada each made that Comstock Lode mining town the launching pad for their careers. One was Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, the Nation’s most famous author. The other was William A.G. Brown, shown here, an African American saloonkeeper who languished in obscurity until Nevada archeologists excavated the site of his drinking establishment. Details of Brown’s life before arriving in Virginia City are scant. Local records list his death there in April 1893 and give his age as 63. This would put his birth at 1830 in Massachusetts and likely in or near Boston, the name he gave his saloon. Although Brown was not born in slavery, his education would have been in segregated schools. Although Boston was the first city in the U.S. to desegregate its public schools, that did not occur until 1855, when Brown was 25 years old. He likely attended one of the “Jim Crow” schools for blacks for at least the time it took to learn to read and write.

Given the sophistication that is attributed to Brown by archeologists who excavated his saloon, he likely was employed as a busboy or waiter at a upscale restaurant or hotel. His acquaintance with imported wines and liquors, his understanding of choice cuts of meat, even the confidence he exhibits in the portrait above, all bespeak a background in a fairly posh eating establishment.

Like Mark Twain, Brown was drawn to Virginia City by the promise of wealth. As one author has put it: “From around 1860 to the late 1870s, the Comstock's mining wealth captured international headlines and Virginia City developed a complex, cosmopolitan community, attracting immigrants from all over the globe. People from North, South, and Central America, Europe, Asia, and Africa came to the mining district, hoping to harness some of its globally renowned glitter of silver and gold.” Virginia City was not a typical Wild West town. It was highly urbanized, cosmopolitan and industrial, with a population that reached 25,000.

At the time of his arrival, Brown was about 32 years old. Why did he choose to begin in Virginia City as a bootblack, a trade identified with youth — “shoeshine boys” — not usually grown men? My guess is that he chose to start that way as way to scope out the possibilities the city might hold for a man of color. In Boston African-Americans had been virtually excluded from the liquor business by the end of the nineteen century. A shoeshine man by mixing with both blacks and whites could get an idea of what economic opportunities might be at hand.

At the time of his arrival, Brown was about 32 years old. Why did he choose to begin in Virginia City as a bootblack, a trade identified with youth — “shoeshine boys” — not usually grown men? My guess is that he chose to start that way as way to scope out the possibilities the city might hold for a man of color. In Boston African-Americans had been virtually excluded from the liquor business by the end of the nineteen century. A shoeshine man by mixing with both blacks and whites could get an idea of what economic opportunities might be at hand.By the time Brown arrived in Virginia City it may have boasted as many as one hundred saloons, but none for the black population of several hundred, who like William were drawn to the Comstock by the hope of a more prosperous life. There he would meet Dr. W.H.C. Stephenson, born in Washington, D.C., and the first black doctor in Nevada; George Cottle, black owner of the successful Virginia City Union Hotel, and John Martin, a trustee of the local African Methodist Episcopal Church. Those community leaders may have encouraged Brown to open what Twain in his newspaper column called “a popular resort for the colored population.”

By 1864 Brown had abandoned his shoeshine stand and opened the Boston Saloon on B Street, a site described as on “an upslope location along Virginia City’s mountainside setting and well beyond the center of town.” African Americans in Virginia City did not reside in a distinct or designated community as did the Chinese population. Instead, blacks occupied homes in locations scattered throughout town, with the majority, as shown on the map here, residing above D Street on the city’s western side.

By 1864 Brown had abandoned his shoeshine stand and opened the Boston Saloon on B Street, a site described as on “an upslope location along Virginia City’s mountainside setting and well beyond the center of town.” African Americans in Virginia City did not reside in a distinct or designated community as did the Chinese population. Instead, blacks occupied homes in locations scattered throughout town, with the majority, as shown on the map here, residing above D Street on the city’s western side.Little is known about the first Boston Saloon. It likely was of wooden construction, rather plain and possibly with the false front common in Western towns. It must have been a successful venture. By 1866, Brown moved from B Street to a second address several blocks away at the southwest corner of D and Union Street. In effect, he had moved from “the sticks” to the center of Virginia City’s entertainment and red light district. Although brothels were plentiful, the district also was the site of Virginia City’s prime opera houses, theaters, and a few respectable drinking establishments.

The birds-eye drawing here is the only known image of Brown’s second saloon, shown inside the red circle. In her book “Boomtown Saloons: Archeology and History in Virginia City,” Archeologist Kelly J. Dixon describes Brown’s saloon as a long narrow building crowded by larger structures on each side with an alley in back: “The building was rectangular with long axis perpendicular to D Street. At the center of the Boston Saloon’s facade, two windows flanked a door. An overhang or awning spanned the entire width of the facade.” The building was constructed of wood.

The birds-eye drawing here is the only known image of Brown’s second saloon, shown inside the red circle. In her book “Boomtown Saloons: Archeology and History in Virginia City,” Archeologist Kelly J. Dixon describes Brown’s saloon as a long narrow building crowded by larger structures on each side with an alley in back: “The building was rectangular with long axis perpendicular to D Street. At the center of the Boston Saloon’s facade, two windows flanked a door. An overhang or awning spanned the entire width of the facade.” The building was constructed of wood. Leveled by the Great Fire of 1875, the site of the saloon became a parking lot for the Bucket of Blood Saloon, one of Virginia City’s later tourist attractions. The excavation by University of Nevada archeologist in 2001 unearthed thousand of artifacts that have produced a great deal of information about the Boston Saloon and its owner.

Leveled by the Great Fire of 1875, the site of the saloon became a parking lot for the Bucket of Blood Saloon, one of Virginia City’s later tourist attractions. The excavation by University of Nevada archeologist in 2001 unearthed thousand of artifacts that have produced a great deal of information about the Boston Saloon and its owner.

They point to the entrepreneurship and sophistication of Saloonkeeper Brown. For example, he was not relying on beer and local “rogut” whiskey to serve over his bar. Shown here is a bottle of French champagne and a shard from a Gordon’s (English) gin found on the site. Another fragment disclosed a soda water from Cantrell & Cochrane of England. These imported items required cross-continent shipping and were pricey.

They point to the entrepreneurship and sophistication of Saloonkeeper Brown. For example, he was not relying on beer and local “rogut” whiskey to serve over his bar. Shown here is a bottle of French champagne and a shard from a Gordon’s (English) gin found on the site. Another fragment disclosed a soda water from Cantrell & Cochrane of England. These imported items required cross-continent shipping and were pricey.  Other finds included a bottle of Dr. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, perhaps the best selling American patent medicine of all times. Like all bitters, the nostrum was heavily laced with alcohol and sold at many high end saloons to those who preferred “medicating” to drinking. Also shown here is a bottle that looks familiar even today. Then and now it held Tabasco sauce. Brown’s saloon was the only archeological site in Virginia City to bear this bottle, invented about 1869. It suggests the proprietor was a trendsetter, early on using a condiment that ultimately would sweep the country.

Other finds included a bottle of Dr. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, perhaps the best selling American patent medicine of all times. Like all bitters, the nostrum was heavily laced with alcohol and sold at many high end saloons to those who preferred “medicating” to drinking. Also shown here is a bottle that looks familiar even today. Then and now it held Tabasco sauce. Brown’s saloon was the only archeological site in Virginia City to bear this bottle, invented about 1869. It suggests the proprietor was a trendsetter, early on using a condiment that ultimately would sweep the country.The most definitive evidence of Brown’s good taste and elevated status was deduced from the animal bones found in the excavation. Of the four local saloons studied, the Boston had the greatest abundance of beef and sheep bones from expensive cuts of meat. Others abounded in the leavings from pork, a cheaper meat, associated with the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. This suggests that many of Brown’s black customers were affluent enough to enjoy an upscale meal and that whites also frequented the Boston Saloon.

Author Dixon is keen to differentiate Virginia City saloons from the “shoot em up” Western drinking establishments popularized by Hollywood. The Territorial Enterprise reported only one incident at Brown’s Boston, occurring in August 1866. Here is one retelling of the original story: “A gunshot pierced the smoky air in the small, boomtown saloon. It came from the poker table, where all but one the players sprang to their feet. One of the players writhed on the floor as blood spilled from his leg. The shot was an accident, caused by a pistol falling from someone's lap and discharging when it hit the floor. Although his leg was sore for a while, the victim survived. Except for the man shot in the leg, who happened to be the only white man in the saloon at the moment, all the participants in this scene were of people of color.”

What is missing here is an emphasis on the fact that men around the card table, of whatever color, were carry loaded firearms on their laps during a card game, an indication that any perceived cheating might result in gunplay — an outcome not too far from the movies. In fact, Brown himself had a gun and knew how to use it.

That was documented by Ronald M. James in his book, The Roar and the Silence. James relates that a woman identified as William Brown’s wife testified in court on his behalf after the saloonkeeper had shot and killed a fellow African-American named John Scott. Court records indicate that for reasons unknown Scott was obsessed with attacking Brown at the Boston. In response to his threats Brown repeatedly asked Scott to leave the saloon. When his assailant refused, he pulled his gun, fired and killed him. Virginia City law enforcement apparently concluded the shooting was in self-defense and Brown was not charged with a crime.

The identity of Brown’s wife remains a mystery. Some believe she was of the common law variety. Author Dixon envisions her working at the Boston serving customers. Others identify her with a well-known Virginia City prostitute. Whoever she might have been, there do not appear to have been any children from the relationship.

Whether it was the shooting incident or another cause, after eleven years in the saloon business, nine of them at the D and Union address, Brown sold the Boston in 1875 at the age of about 45 and retired with his profits. By so doing he avoided the huge fire that same year that leveled the Boston and much of Virginia City. The saloon was not rebuilt. Brown’s activities in ensuing years have gone unrecorded. Apparently continuing to living in the Comstock, he died 18 years later, his place of interment unrecorded.

By this time Mark Twain was world famous as the author of “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn.” He had left Virginia City and the Territorial Enterprise in 1864, crossing paths with William Brown for only about two years. Yet they may have had an association. Twain’s friends, including his newspaper editor, accused him of stealing a coat and boots and trading them to Brown for a bottle of whiskey, described as tasting “vile.”

While never achieving the fame of the author, Brown has more recently written his name in the history books as a pioneering African-American who ventured West and succeeded as an entrepreneur. His achievements occurred even as Virginia City was going through economic cycles that led downward and the small black community often was subjected to indignities. Today a historical plaque at the Boston Saloon site, explains: “Prejudicial laws and racism placed hurtful restrictions on the African-Americans of Nevada.”

Note: This post was drawn from a variety of sources, the principal ones being Kelly J. Dixon’s 2005 book previously cited and “Archeology of the Boston Saloon,” published by ScholarWorks@UMass, Amherst, 2006. A majority of the photos here also originally came from the Dixon book but also have been reproduced on other Internet sites.

Comments

Post a Comment