Tex Rickard, Nome, Alaska, and Goldfields, Nevada

While a toddler, Rickard and his family moved to Texas, where soon after his father died. Forced to truncate his education to help with family finances, at eleven years old he went to work as a cowboy on the Texas frontier and took part in several long cattle drives. By the age of 23, having indicated unusual abilities and earned the nickname “Tex,” Rickard, shown right as a youth, was elected town marshall of Henrietta, Texas. He married in 1894 and had a child but both his wife and baby died within a year.

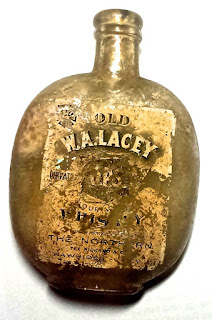

While a toddler, Rickard and his family moved to Texas, where soon after his father died. Forced to truncate his education to help with family finances, at eleven years old he went to work as a cowboy on the Texas frontier and took part in several long cattle drives. By the age of 23, having indicated unusual abilities and earned the nickname “Tex,” Rickard, shown right as a youth, was elected town marshall of Henrietta, Texas. He married in 1894 and had a child but both his wife and baby died within a year. Perhaps grieving over his losses and drawn by the discovery of gold in Alaska in November 1895, Rickard headed for the gold fields of Alaska where he and a partner staked and later sold a valuable claim. He used the funds to open a saloon, gambling hall and hotel in Dawson City, Canada, that he called “The Northern,” a name he subsequently gave to several of his saloons.

Perhaps grieving over his losses and drawn by the discovery of gold in Alaska in November 1895, Rickard headed for the gold fields of Alaska where he and a partner staked and later sold a valuable claim. He used the funds to open a saloon, gambling hall and hotel in Dawson City, Canada, that he called “The Northern,” a name he subsequently gave to several of his saloons.

Possibly suffering from the deaths of his wife and child and a second failed marriage, in Dawson Rickard began to drink and gamble heavily. It cost him his share of the saloon and he was forced to work as a poker dealer and bartender in the Monte Carlo Saloon. It was there Tex with a partner first began to promote boxing matches. But gold still beckoned. In the spring of 1899, reputedly with only $35 to his name, Rickard headed to Nome, Alaska, where a strike had been reported.

Apparently with borrowed funds, Rickard opened a saloon and gambling house in Nome. By the fall of 1899 he had cleared $90,000 ($2.2 million equivalent today). By the following year, as nugget-bearing miners continued to drink and gamble at his establishment, he was $100,000 to the good and within five years was worth a half million. Possibly because “The Northern” was already the name of a Nome saloon, Rickard may have called his “The Southern.” The cabinet card above is of an Alaska saloon of that name with Rickard’s name prominently displayed.

Apparently with borrowed funds, Rickard opened a saloon and gambling house in Nome. By the fall of 1899 he had cleared $90,000 ($2.2 million equivalent today). By the following year, as nugget-bearing miners continued to drink and gamble at his establishment, he was $100,000 to the good and within five years was worth a half million. Possibly because “The Northern” was already the name of a Nome saloon, Rickard may have called his “The Southern.” The cabinet card above is of an Alaska saloon of that name with Rickard’s name prominently displayed.

One author has commented: “Physically, Tex Rickard was a most engaging person, a tall man with small twinkling eyes set into a bland, smooth-skinned face. He had the gamblers’ thin-tipped trap mouth, an infectious, boyish smile and an impish expression.”

In Nome, Rickard met and became a lifelong friend of Wyatt Earp, who for a time owned a competing saloon. Earp, shown here, was a boxing fan and previously had been hired to referee matches. Their relationship may have whetted Tex’s appetite for the boxing game. Later Rickard would hire Wyatt’s brother, Virgil, as a bartender and then saw that he was made a deputy sheriff just before that Earp brother died of pneumonia.

As had happened in Dawson, the gold soon ran out in Nome. Rickard, who had invested most of his riches in mining properties lost most of his wealth and saw the client flow at his saloon and gambling hall slow to a trickle. This time Tex looked south to Goldfields, Nevada, 247 miles southeast of Carson City. Gold had been discovered in the vicinity in 1903 and the site had become a boomtown. The yellow stuff was making prospectors rich overnight and, as usual, looking for a place to spend their cash.

By now a thoroughly experienced proprietor, Rickard in 1904 knew just what Goldfields’ spenders needed. In 1904 he packed up and moved to Nevada. Together with two partners, he opened the Northern Saloon.

By now a thoroughly experienced proprietor, Rickard in 1904 knew just what Goldfields’ spenders needed. In 1904 he packed up and moved to Nevada. Together with two partners, he opened the Northern Saloon.  It was the most elaborate of any of his watering holes, featuring 12 bartenders, 14 gaming tables, and 24 dealers. According to its bookkeeper, Tex’s place made $30,000 monthly from the tables and $12,000 monthly from liquor. A photograph from the University of Nevada, Reno, shows the interior of the Northern. It is teeming with customers, one of them gambling one-on-one with a dealer.

It was the most elaborate of any of his watering holes, featuring 12 bartenders, 14 gaming tables, and 24 dealers. According to its bookkeeper, Tex’s place made $30,000 monthly from the tables and $12,000 monthly from liquor. A photograph from the University of Nevada, Reno, shows the interior of the Northern. It is teeming with customers, one of them gambling one-on-one with a dealer.

Wealthy once again, Rickard built the most impressive brick house in Goldfields, one that still stands. Shown below, the dwelling boasted lead glass windows and a white picket fence. Tex furnished it lavishly with oriental carpets, expensive wallpaper and fine decoration. It boasted the only lawn in Goldfields and neighbors were said to have turned out to watch whenever Rickard cut the grass.

According to one possibly apocryphal account, the house lacked a kitchen because the saloonkeeper lived there alone and took all his meals out. At the time, however, Tex had wed again. She was Edith May Haig of Sacramento, California, and the couple had one daughter who died in 1907. They were married until Edith’s death but it is possible she did not accompany him to Goldfields — or deign to cook.

By this time Rickard had achieved some recognition as a fight promoter. As shown here, he sponsored minor bouts held in the town square next to the Northern Saloon. Tex, however, had his sights on bigger goals. In December 1909, Rickard and a partner won the right to stage the world heavyweight championship fight between James J. Jeffries and Jack Johnson, billed as “The Fight of the Century.” Although Rickard had planned to hold the fight on July 4, 1910 in San Francisco, opposition caused him to move it to Reno, Nevada. The bout gained national attention and brought recognition to Rickard as a fight promoter. Tex and his partner made a profit of about $120,000 on the fight, won by a knockout by Johnson.

By this time Rickard had achieved some recognition as a fight promoter. As shown here, he sponsored minor bouts held in the town square next to the Northern Saloon. Tex, however, had his sights on bigger goals. In December 1909, Rickard and a partner won the right to stage the world heavyweight championship fight between James J. Jeffries and Jack Johnson, billed as “The Fight of the Century.” Although Rickard had planned to hold the fight on July 4, 1910 in San Francisco, opposition caused him to move it to Reno, Nevada. The bout gained national attention and brought recognition to Rickard as a fight promoter. Tex and his partner made a profit of about $120,000 on the fight, won by a knockout by Johnson.

Despite the rich return of the Jeffries-Jackson bout, Rickard announced to the press that he was “through with the business of prize fighting.” He sold the Northern and his house in Goldfields and sailed to Latin America. There he acquired land in Paraguay, managing huge a cattle ranch for five years. Once again his investment proved faulty, the cattle business failed, and Rickard is estimated to have lost about a million dollars.

By the time of his return to the United States in 1916, Rickard had revised his thinking about the fight game. That same year he promoted a heavyweight bout between Jess Willard, the “The Pottawatomie Giant” and Frank Moran in New York City at Madison Square Garden. He followed in 1919 by with the famous bout in Toledo, Ohio, between Willard and Jack Dempsey, shown here, and promoted the 1927 rematch at Soldiers Field in Chicago. The second match brought in the first $2-plus million gate and was the first to feature a $1 million purse. Rickard made made money on both fights. His biggest payday, $550,000, resulted in 1921 from matching Dempsey against George Carpentier, “The Idol of France” in Jersey City, New Jersey.

By the time of his return to the United States in 1916, Rickard had revised his thinking about the fight game. That same year he promoted a heavyweight bout between Jess Willard, the “The Pottawatomie Giant” and Frank Moran in New York City at Madison Square Garden. He followed in 1919 by with the famous bout in Toledo, Ohio, between Willard and Jack Dempsey, shown here, and promoted the 1927 rematch at Soldiers Field in Chicago. The second match brought in the first $2-plus million gate and was the first to feature a $1 million purse. Rickard made made money on both fights. His biggest payday, $550,000, resulted in 1921 from matching Dempsey against George Carpentier, “The Idol of France” in Jersey City, New Jersey.  By now firmly ensconced in New York City, a rich man and a world renowned fight promoter, Rickard continued to build his legend. His trademarks were a soft, light-colored fedora hat, the snap brim turned down, a straight gold-headed malacca cane and a cigar. In 1926 he promoted the Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney fight in Philadelphia. The bout attracted a world record crowd of 135,000 and earned $1,895,000. By now fabulously wealthy, Rickard also founded and owned the New York Rangers hockey team and built the third version of Madison Square Garden in Manhattan.

By now firmly ensconced in New York City, a rich man and a world renowned fight promoter, Rickard continued to build his legend. His trademarks were a soft, light-colored fedora hat, the snap brim turned down, a straight gold-headed malacca cane and a cigar. In 1926 he promoted the Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney fight in Philadelphia. The bout attracted a world record crowd of 135,000 and earned $1,895,000. By now fabulously wealthy, Rickard also founded and owned the New York Rangers hockey team and built the third version of Madison Square Garden in Manhattan.

In 1925, Rickard’s wife of 23 years, Edith Mae, died in New York. Earlier Tex had met Maxine Hodges, a former actress 33 years his junior. The couple married on October 7, 1926, in Lewisburg, West Virginia. On June 7, 1927, the couple's daughter, Maxine, was born. Tex had little time left to enjoy his new baby. In December 1928 while he was in Miami arranging a boxing match he was felled by an appendix attack. Complications occurred during the course of a likely botched operation and Rickard died on January 5, 1929, at the age of 59. His body was returned to New York and he was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

Sportswriter Davis J. Walsh memorialized him: "Rickard wasn't merely associated with boxing; he was boxing itself. He took it out of the back rooms and dropped it into the laps of millionaires. He established a monopoly by cornering its star performers. He made it the biggest money business of all professional sports.…” My analysis of Rickard’s career suggests that his years as a saloonkeeper were crucial to his success. Blessed with a genial personality and the ability to understand what his customers wanted, Tex applied the lessons he learned behind the bar to a much larger stage and found they worked for him there as well.

Comments

Post a Comment